Nakedness and Nature: the Nymph in Art History

By: Corrie Hendricks

Recently, John William Waterhouse’s “Hylas and the Nymphs” was temporarily removed from the Manchester Art Gallery. This work, a notable example of Pre-Raphaelite painting, depicts a pond full of naked water nymphs imploring a young man to join them for a swim. The painting was removed from the walls of the gallery and replaced with a prompt, asking museum-goers to engage in conversations surrounding “how we display and interpret artworks in Manchester’s public collection”. This event has sparked intense debate concerning whether it was an artistic act or merely a form of censorship in a particularly sensitive sociopolitical atmosphere. The painting has since been placed back on display.

On a completely unrelated note, I have been really into the depictions of nymphs lately.

I wish I could say my interest was sparked by this hotly debated issue or, better yet, was some kind of academic inquiry into representations of women. The truth is, spring is on the horizon, flowers are blooming, and I just want to look at pretty paintings of mythological nature deities. However, by making my way down this rabbit hole, I have unintentionally learned a few things concerning the complicated history of the nymph.

So, dear reader, I welcome you to join me on a short “ooOoOoh that’s pretty” meets “whoa that’s problematic” tour of nymphs in art history.

John William Waterhouse, Hylas and the Nymphs, Oil on Canvas, 1896

A Brief History of the Nymph

According to ancient Greek mythology, nymphs or nymphai were minor goddesses of nature. They were less powerful than gods but were still called upon to attend assemblies on Mount Olympus. Nymphs oversaw natural phenomenon of all kinds. Different types of nymphs presided over different aspects of nature which is why we have sea nymphs, forest nymphs, mountain nymphs etc. In many ways, the nymph is the mythological personification of natural creation.

Naiad Ismene & The Dragon, Paestan Red Figure Krater, c. 360-340 B.C.

Belief in nymphs continued into the early years of the twentieth century, particularly in Greece. Modern interpretations of nymphs tended to focus on their mischievous and dangerous characteristics. For example, if a human stumbled upon a group of water nymphs bathing in a pool, they may fall victim to their powers and be struck dumb, infatuated, or even mad. The nymph quickly became associated with the “femme fatale” archetype, a theme we see in many of the visual representations of nymphs to this day.

According to modern interpretation, nymphs were considered highly sexual creatures and, therefore, often demonized. This characterization lead to the use of the term nymphomania in modern psychology to describe abnormally excessive sexual behavior. This term was used strictly for women, although the much lesser known satyriasis was used to diagnose the same issue in men. Unsurprisingly, satyriasis was rarely diagnosed, probably because such behavior in men is less likely to be viewed as a problem. The term has since fallen out of favor in the medical community and has been replaced with the gender-neutral hypersexuality.

Ultimately, these magical creatures come with a lot of creative power…and a lot of baggage.

“Hylas and the Nymphs” by John William Waterhouse

Let’s begin our journey with the image everyone’s talking about, J.W.W.’s “Hylas and the Nymphs”.

The nymphs are painted in natural tones that blend in with the surrounding landscape, emphasizing their relationship with the natural world. Hylas, on the other hand, sticks out due to his blue and red robe. The juxtaposition of these colors, as well as the clothed vs. the unclothed, represents the opposition of civilization and the natural world. The viewer’s eye is drawn to the nymph at the center of the composition. Her hair is pinned back with a flower. She grasps onto Hylas’ arms in a way that is both tender and desirous. She looks into his eyes with a gently hypnotic gaze. There is something hauntingly sensual about the nymphs in the painting. They are depicted as a Victorian-age femme fatales (which is one of the reasons this painting was chosen for the Manchester Gallery’s experiment). Interestingly, Waterhouse and other Pre-Raphaelite painters were known for exploring the theme of the femme fatale in their work.

“Hylas and the Nymphs” depicts a scene from classical mythology. Hylas, an Argonaut warrior, is tempted by the nymphs of the spring of Pegae. As the story goes, Hylas was kidnapped by the nymph Dryope never to be seen again, deeply upsetting Hercules. At least one variation of the tale has Hylas falling in the love with the nymphs. Perhaps this is a case of Stockholm syndrome…or maybe Hylas would rather spend his youth with a group of beautiful and powerful lady deities than search for a Golden Fleece.

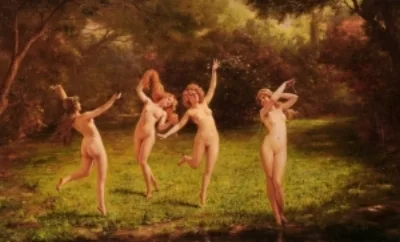

“Spring” by Charles Joseph Frederic Soulacroix

Charles Joseph Frederick Solacroix, Spring, date unknown

I don’t have a lot of information on this one, I just find it delightful.

Solacroix was a French-Italian fresco painter in the late nineteenth century. He typically painted romantic genre scenes of the upper-class, the focus of which was decadent costuming. With the exception of some romantic elements, this image is definitely not that. Four naked female characters are frolicking in a meadow, arms outstretched and hair flowing in the wind. Each figure appears gleefully comfortable in their body, celebrating the sunny spring day.

This image calls to mind Albrecht Durer’s “Four Witches”, an engraving of four naked women dancing in a circle. There are several reasons the blissful ladies of Solacroix’s Spring are placed in the “nymph” category as opposed to the “witch” category. For one, nymphs are commonly associated with spring (even though the taxonomy of nymphs includes everything from flower nymphs, to wine-press nymphs, to underworld nymphs). Also, over time, the nymph has become associated with innocence and youth, even though that is not a necessary characteristic according to the mythology.

Albrecht Durer, The Four Witches, engraving, 1496

Comparing these images highlights the similarities between nymphs and witches, particularly with regard to their transformation at the hands of the patriarchy. Nymphs and witches are both powerful, magical entities that embrace feminine energy and are in touch with the natural world. Similarly, they have both been used to demonize powerful and sexual women. To quote Broad City’s Ilana Wexler, “Witches aren’t monsters, they’re just women who orgasm and giggle and play in the night and that’s why everyone wants to set them on fire...because they’re fucking jealous.” Whether the figures in the image are witches or nymphs…this is a springtime celebration I want to be a part of.

“Nymph on a Rocky Ledge” by Childe Hassam

Childe Hassam, “Nymph on a Rocky Ledge”, 1886

Childe Hassam was an American Impressionist painter working in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He was considered incredibly influential in promoting the Impressionist style in the United States. He was known for his ability to depict the excitement of urban areas as well as the calm of a coastal retreat.

I loooove this image. “Nymph on a Rocky Ledge” is strikingly different from many popular images of nymphs at this time, particularly those painted by the Pre-Raphaelites. The nymph is leaning casually on a rock formation, gazing out at the sea. She dons only a flower crown. Hassam’s generous brush strokes suggest that her naked body is either emerging from or blending into the rocks she stands against. There are no other characters in the scene, disassociating her from both her typical crew of fellow nymphs and any possible victim. In this image, the nymph is not the femme fatale, nor is she excessively innocent or sensual. She is just a chill-ass nymph by the sea.

“Faun and Nymph” by Hans Zatzka

Hans Zatzka, Faun and Nymphs, c. 19th century

Zatzka was an Austrian painter in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Much of his living was made painting imagery for church interiors. He is often considered a painter of fantasy, and many of his images illustrate a clear influence of the Rococo style.

Hans Zatzka’s Faun and Nymphs is more sugary than the entire bag of Sour Patch Kids I just gobbled. Vibrant pastel colors, flowing fabric, and lavish flower arrangements make the natural world appear decadent af. The turquoise sea merges with a wave of pink and yellow flowers, possibly suggesting that this is a meeting of a sea nymph and flower nymph.

In this image, the romantic interest of the nymph is another mythological creature instead of a mere mortal. In Roman mythology, the faun is a desirous half-human, half-goat creature. His lustful appetites make him the obvious male counterpart to the nymph. While the nymph is often depicted as the instigator, the faun seems to be taking the lead in this mythological courtship. There is nothing suggesting that the nymphs in the painting are dangerous or malicious. Likewise, the relationship between the nymph and faun is not depicted as debaucherous, even though these mythological characters are both associated with sexual indulgence. In Zatzka’s interpretation, any wickedness that is commonly associated with nymphs and fauns is shrouded by fluffy brush strokes and diaphanous fabric.

Embrace Your Inner Nymph

Nymphs make their way into countless scenes throughout art history as both central and supporting characters. The various depictions of these mythological creatures are often layered with nuance surrounding society’s views concerning women, sexuality, and the wild unknown. Looking at the nymph through a monstrous lens places the creature in a position of depravity and malicious intention. In this context, the nymph may represent fear of the unknown. On the other hand, the nymph can be an empowering figure, connecting women to the beauty and power of the natural world and expressing female sexuality in way that was considered socially acceptable at the time.

In contemporary society, free-spirited ladies that embrace their sexuality are much more normalized than they were the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. However, the association of these characteristics with the femme fatale archetype lives on. However, like all women, nymphs are much more multidimensional and can't be defined by their sexual behavior. Nymphs are allegories of all aspects of nature with a rich mythological past. Therefore, the image of the nymph has the potential to represent many many layers of the human experience.

Also, with festival season coming up, nymphs of art history are excellent fashion inspo.

Sources:

Thetate.org.uk, "A short history of nymphomania"

Artble.com, John William Waterhouse's "Hylas and the Nymphs"

Corrie is a host of the Art History Babes podcast. She is a dancer, wonder junkie, and mama to a sweet bun named Pancake Jefferson. In her free time she enjoys reading people their horoscopes and watching time-lapsed videos of flowers blooming.